Living in a time of cheap gas

Fuel may seem expensive but today’s 1950s prices may not survive global climate disasters and political unrest.

The American Automobile Association expects almost 80 million people will have hit the highways during the Thanksgiving holiday. That would be a record, blowing through the numbers in pre-pandemic 2019. Many drivers grumbled as they pulled out of holiday traffic jams only to pay close to $70 to fill their 22-gallon SUV tank, given current prices of around $3 per gallon.

People consistently complained about high gas prices in the runup to this year’s election, even though the price spike of 2022 has vanished into the rearview mirror. The miles being put on odometers this holiday—as well as the larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles Americans are buying—eloquently convey what most people think about gas costs. They don’t care.

Gas is cheap

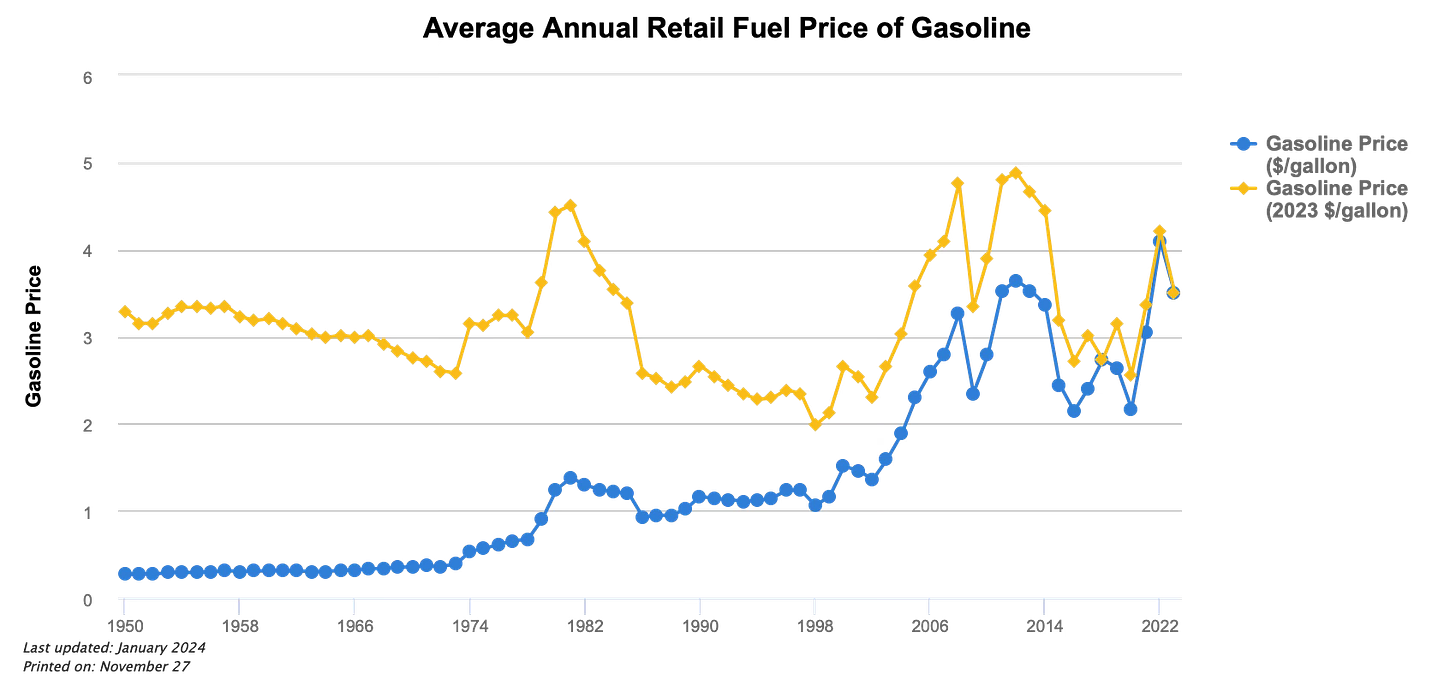

First let’s dispel the myth of high-cost gas. In 1950, gas cost 27 cents per gallon. I wasn’t born yet but I am old enough to remember two-digit gas prices. Those were the days!

Nah. Inflation adjusted, today’s prices are essentially the same as in 1950. Surprised? I was. But then I recalled my mother cruising the suburbs to knock off a couple of cents per gallon, just as people do today—and she was driving a 60-hp 1950 Plymouth that bobbed and swayed alarmingly when it could be nudged up to 60 mph going downhill.

Part of the obsession with fuel prices is lazy media practice. Whenever prices jump—and they do from time to time—news outlets depict a “crisis” in apocalyptic terms and zoom the camera in on tales of horror: people who can’t get to work, get medical treatment, or buy groceries because they can’t afford to fill their tanks. I was both amused and annoyed by one such story illustrated with a photo of a glum driver filling his classic 1960s Chevy Impala—at about 12 mpg, not a good choice if cost is an issue.

Most people spend an all but meaningless amount on auto fuel—from 3% to 5% of typical household expenses. The higher burdens, unfortunately, fall on the lowest incomes. And too many low-income people have no other choice, which is a problem that can be fixed by building neighborhoods that offer auto alternatives.

Though gas is not expensive, prices can be volatile, bumping up and down regularly by 25- or 50-cent increments. Since the 1970s much higher spikes have periodically occurred. That volatility is one reason people feel gas is expensive even though objectively it is not.

Volatile gas prices are a fact of life, and if people made choices based on that understanding, the landscape of American transportation might look different. Prices lurch upward unpredictably, and people rarely can know how high costs will rise nor how long price spikes will last.

The roots of energy “crises”

Until 1974 gasoline prices were stable, even after years of a vast global increase in consumption. That year the recently formed Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)—mainly large middle eastern oil producers—embargoed production to show their displeasure with the defense of Israel by the U.S. and other countries, which had been invaded by Egypt and Syria.

The loss of imported supply led to long lines at the pump, with average prices spiking to $4.50 in today’s dollars. The low mileage of American cars in that year and during the second embargo in 1980, made those events far more disruptive than in any price spike since. Gasoline didn’t go very far given weighty, 20-foot long cars and low-efficiency engines. The first embargo not only threatened a U.S. economy that even then offered few alternatives to driving for essential tasks. America’s extravagant appetite for oil undercut U.S. power on the global stage and was partly responsible for voters turning out Jimmy Carter after just one presidential term.

Yet the embargo traumatized our car-crazed nation sufficiently to bring on the first fuel efficiency standards. There have been fits and starts, but far greater efficiency made possible lumbering SUVs that—relatively speaking—did not break the bank at fill-up time.

Americans have forgotten that a peak in gasoline prices (which doubled between 2002 and 2008, spurred in part by the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and fighting insurgents over eight ensuring years) helped precipitate the the Great Recession even if it was a housing boom built on a mortgage-making house of cards that made the bust so deep and long.

Fracking added huge new supplies and prices dropped in the teens until the slow-moving economic recovery became widespread near the end of the decade as Americans shifted to larger less-efficient vehicles.

In 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine and western nations cut off access to its ample gas and oil supplies, upending global supply chains. That coincided with a rapid rise in demand as people took to the roads with a vengeance after pandemic shutdowns ended. These disruptions proved temporary, as global suppliers adjusted (including China and India keeping Russia in the oil and gas export game).

What is the through line here? Political unrest if not outright war among petro states is the clearest culprit for gas-price spikes. The countries deemed by the the oil-patch President George Bush as an “axis of evil” after the 9/11 attacks (which included oil-state terrorists) were two petro-states, Iran and Iraq, as well as North Korea.

These days a similar axis is deemed to be Iran and Russia (two oil producers), with, inevitably, North Korea. Iran backs Hamas and Hezbollah as well as the Houthis, who periodically interrupt oil shipments off the coast of Yemen.

Oil wealth, seemingly a gift, is more often a corrupting curse. Venezuela has collapsed. Nigeria can’t resolve conflicts among its indigenous factions. The Middle Eastern giants are ruled by authoritarian elites.

U.S. politicians hate to talk about the enormous human consequences of Americans’ profligate use of oil and gas because it makes peoples’ petulance about gas prices look selfish. Candidate Kamala Harris and Democrats learned (as Jimmy Carter did) that voters are more than willing to punish officials who won’t or can’t tamp down price spikes. (Given the widespread assumption that cheap gas is akin to a human right, opportunistic politicians proposed to suspend road taxes during 2022’s price spike, when they should have encouraged less use to drive prices down.)

Can gas stay cheap?

Here’s the takeaway: anyone whose budget can’t tolerate gas-price spikes should be looking hard at how to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels. Treating cheap gas as an entitlement is getting increasingly difficult given rising global political and environmental forces that are knocking on Americans’ doors.

With natural disasters—floods, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes, among them—bulked up by global-warming emissions from fossil fuels, expect more supply chain interruptions, such as the slowdown of the Panama Canal that began in 2023 thanks to a drought.

Political instability, sometimes involving oil producers directly but often due to natural disasters, water wars, and collapsing agriculture—these worsened by global warming as well—have induced massive migrations. For many of those millions, the U.S. is their preferred destination.

U.S. driving habits cause hordes to crowd the southern border? Not no.

For decades oil apologists have said that America can be assured of consistently low fuel prices by becoming “energy independent”—in other words, by producing more oil and gas than it consumes. Thanks to fracking this goal has come to pass. America is now the world’s largest oil producer. That status did not prevent those 2022 lines at the pump and retail prices briefly spiking to near $10 per gallon in places. Exporting some five trillion British thermal units of oil annually locks the U.S. into the global oil supply network, so our gas markets are vulnerable whenever supply is throttled for whatever reason.

You are in charge

In contrast to high rents, punishing interest rates, and ridiculous health-care costs, auto fuel is one of the few expenses that people have quite a lot of control over. The law of supply and demand tells us to use less fuel to assure low costs, but Americans only choose to use less when prices spike. Weaning ourselves of the fossil-fuel habit comes with a myriad of benefits besides saving money. Readers will know what they are: fewer road deaths, cleaner air, lower greenhouse-gas emissions, fewer traffic jams.

Also the joys of the open road are not what they used to be. Those empty, twisty mountain roads and vehicles skidding across empty deserts that dominate auto advertising are a reality for almost no one. We got sold on large, four-wheel-drive vehicles that can cruise effortlessly at 90 mph and clamber up mountainsides. But we pilot them from parking lot to parking lot along wide, gently curved suburban arterials that would not challenge the worn-out jalopies of my youth. With today’s less-predictable traffic patterns anyone can find themselves stalled in traffic in the middle of nowhere with the nav app showing that 20 minute delay just became 30.

Owning and driving a vehicle is not likely to get cheaper, nor more pleasant no matter what politicians say.

The best way to keep fuel prices low is to simply consume less of it. Though annoying—not to mention anathema to a lot of people—this is not a paradox, simply the operation of supply and demand.

Are you angry about gas prices? Or just want to do your part? Unlike rents, mortgage rates, credit-card interest, and health care costs, gas is among the very few household expenses that any of us can substantially lower. Here’s how.

Live where you can drive less. People who reside in a relatively dense neighborhood where they can conveniently walk, bike, or step onto a bus or train need drive less or not at all, which can save thousands of dollars annually. The dirty little secret of many built-up places: you can get around faster on a bike then by any other mode because you can skirt traffic jams. Even in New York City, I feel the true freedom of the open road only on a bike.

That said, the demand for pleasant walkable districts far outstrips demand and so they tends to be expensive. The sclerotic real-estate development industry isn’t set up to build such neighborhoods, many cities are leery of density, and policies on transportation and housing finance are stuck in the 1950s.

Now for those who like a house, a big yard, or even acreage, who am I to deny it? (I just don’t like to subsidize it…) Understand that you are locking yourself into an auto-centric world where you cede enormous amounts of space to vehicles and your destiny to the unstable politics of petro-states. It is increasingly difficult to escape the skyrocketing tab for insurance. You may get stuck with tolls that are coming to a highway near you, if they haven’t already, and higher fuel taxes because they have not risen to match the rate of inflation. (Indeed, the federal fuel tax was last increased in 1992!) Someday the piper has to be paid. And when you blanch at the monthly cost, don’t blame politicians or evil oil companies. As long as the tradeoffs work for you, pay your share and own it.

Choose a high mileage vehicle. Isn’t this a no-brainer? People, especially in recent years, have steadily moved away from lower-cost, more efficient smaller sedans not just to SUVs (which are innately less fuel efficient) but to larger SUVs and pickup trucks with more powerful engines. For all the complaining, this trend is evidence that Americans don’t care about fuel prices.

These days smaller vehicles are more comfortable than ever as well as quieter, quicker and equipped with advanced safety and convenience features. Hybrid vehicles (many of which pay back their extra cost quickly) can achieve 50 mpg. So-called small SUVs—a relative term—are roomy and comfortable and get mpg in the 30s if hybrids.

On the other end of the spectrum are large SUVs that go only 14 miles on a gallon. Full-sized pickups are in the same realm. They are much larger and more powerful than even the most extravagant wagons and pickups of the oil-embargo era, but the fact that they get roughly the same mileage does not feel like progress to me.

Bring skepticism to the car lot. Do monthly Costco runs justify the cost and bulk of a Chevy Suburban? If you are not a builder or obsessive DIYer, what are you doing with a pickup? Would you change your habits if gas cost $8 per gallon? (It’s not out of the question. Much of the rest of the world pays more.)

Disconnect from fossil fuel tyranny. Many electric vehicles (EVs) have startlingly fast acceleration; their handling can be superior to vehicles with internal combustion engines (nowadays called ICEs), will cost you much less to operate and need fewer repairs. Yet buyers are shying away from EVs. Give them a hard look even if you are a skeptic; many of the criticisms are overblown. EVs will be essential to suburban resilience as climate-change horrors grow. The mass transition to EVs is inevitable; the question is whether we will drive American EVs or ones made in China, which is going all-out to exploit the vast market that American ideology-crazed right wingers appear ready to forsake.

Whatever choices you make, assuming that prices will jump is a prudent way to take the future in hand rather than just let it just happen to you.